Hippolytus Returns Home a Martyr

On the Day August 13 236AD

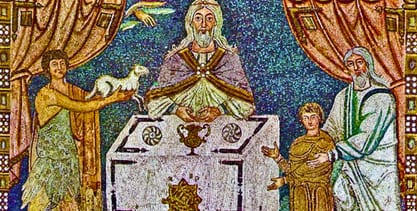

Khen LimEarly Church Fathers (Image source: Reformed Resources)

The Early Fathers of the Church weren’t just stalwarts of the

Gospel of Jesus Christ; they also took the commission to spread the Word

seriously. They made their name defending the Church through apologetic

writings and inspired by Paul, they fought hard against the myriad heresies

that sprouted through the early centuries of fledgling Christianity.

These were

men whom history calls the Apostolic Fathers for they not only gave special witness

to the faith but many, as a result, gave their lives as martyrs.

Early Fathers wrote much about the early Church and yet many Christians

today remain unfamiliar with much of their work. To give the reader an idea of

who some of these prolific Fathers were, here’s a truncated list:

-

Clement of Rome

(?-101AD), executed under Emperor Trajan by being tied to an anchor and thrown

into sea; known widely as the first Apostolic Father of the Church

-

Ignatius of Antioch (c35-c108AD),

possibly thrown to the lions in the Colosseum under the Roman Empire; known as

the second of the three chief Apostolic Fathers of the Church

-

Polycarp of Smyrna

(69-155AD), tied and burned at the stake and then stabbed when the fire failed

to touch him under the Roman Empire; known as the third of the three chief

Apostolic Fathers of the Church

-

Justin the Martyr

(100-165AD), condemned, scourged and beheaded alongside six of his students for

refusing to sacrifice to the Roman gods

-

Irenaeus of Lyons (130-202AD),

possibly made a martyr under Septimius Severus (though not confirmed)

-

Tertullian (c155-c240AD), died

peacefully; known as the Father of Latin Christianity and Founder of Western

Theology

-

Origen Adamantius (185-254AD),

imprisoned by Emperor Decius and then tortured but was released after the

emperor’s death though died shortly after; regarded as a Church Father

-

Cyprian of Carthage

(200-258AD), beheaded after he blindfolded himself on the orders of the

proconsul Galerius Maximus

-

Athanasius of Alexandria

(296-373AD), although died peacefully in his own bed surrounded by his faithful

supporters, he had endured five exiles; known widely as ‘Father of the Canon’

-

Ephrem the Syrian

(c306-373AD), died from sickness and exhaustion while ministering to victims of

the plague; known as ‘Harp of the Holy Spirit’

-

Cyril of Jerusalem

(313-386AD), died peacefully after returning from exile, having been banished

from Jerusalem by the Arian Emperor Valens nineteen years earlier

-

Hilary of Poitiers

(300-368AD), no cause of death given; known as ‘Hammer of the Arians’ and

‘Athanasius of the West’

-

Gregory the Great (c540-604AD),

died after being lamed by arthritis; known to many Gregory the Dialogist (owing

to his Dialogues)

By being Early Fathers of the Church, they were the ones who

laid the foundation for modern Christianity as we know it. Many came after them

through the many centuries leading to today but without these Early Fathers,

things would not have been the same. And in light of all that, one other name

must also be put forth.

He is Hippolytus of Rome.

He is Hippolytus of Rome.

Persecution of Christians in Rome depicted in The Christian Dirce by Henryk Hektor Siemiradzki in the National Museum in Warsaw (Image source: Trip Advisor)

In the days of the early Church, believers in the city of Rome

were solemn. We of course know that some two hundred years earlier, the Apostle

Paul preached in Rome and from his letter to the Romans, which he wrote from

Greece sometime between 56AD and 58AD, he offered us a view of his concerns for

the new Christians who had been there earlier. Slightly before then, Emperor

Claudius had set the tone for Christian persecution in 49AD, beginning with the

expulsion of the Jews among whom were Aquila and Priscilla (Prisca in Rom

16:3).

By the time of the second century, very little had changed in

terms of the persecution. Christians continued to be executed and therein began

the ‘witnesses’ who were then called martyrs.

There were two such witnesses who had died in exile and on this day, August 13, one-thousand seven-hundred and eighty-one years ago, in 236AD, both had come home to be laid to rest. Today, it is on August 13 that the Roman Catholic Church commemorates Hippolytus together with Pontian.

There were two such witnesses who had died in exile and on this day, August 13, one-thousand seven-hundred and eighty-one years ago, in 236AD, both had come home to be laid to rest. Today, it is on August 13 that the Roman Catholic Church commemorates Hippolytus together with Pontian.

Christian slaves in Sardinia mines (Image source: Christian History Project)

In the time of Emperor Maximinus the Thracian (173-238AD),

both Pontian and Hippolytus were exiled to the island of Sardinia in 235AD. Since

226BC when Carthage surrendered it to the Romans, Sardinia had been the empire’s

third most important region – after Spain and Brittany – for mining activity.

By 190AD, the Roman island had resorted to the use of slaves and prisoners

called ‘damnatio ad effodienda metalia’

(tr. condemned to quarry mining) to do the dirty work.

There Pontian and Hippolytus were subjected to harsh slave labour,

toiling in the mines where they allegedly died. Now under Pope Fabian (200-250AD),

their bodies were repatriated for proper interment in Rome. Pontian was laid to

rest in the tomb of Callixtus (d.222AD) who, like him, was also an earlier

Bishop of Rome.

That of Hippolytus’ – also a bishop in or near Rome – was to be buried in a cemetery on the Via Tiburtina (tr. Tiburtine Road) with his funeral conducted by Justin the Confessor (d.269AD) who himself was beheaded some thirty-four years later.

That of Hippolytus’ – also a bishop in or near Rome – was to be buried in a cemetery on the Via Tiburtina (tr. Tiburtine Road) with his funeral conducted by Justin the Confessor (d.269AD) who himself was beheaded some thirty-four years later.

While history records little about Pontian, we do have

Hippolytus’ account. Although considered the most important theologian of the

Roman Church up till then, much of his work had remained under the radar for

centuries thereafter. While some said that was because of his criticism of the

bishops of Rome, it was more likely because, as a Greek, he wrote in his mother

language, which, by then, many in the Western civilisation had lost the ability

to read.

Of his many books, his best known, like those of the Early

Fathers, was one he wrote against heresy called the ‘Refutation of All

Heresies.’ In it, Hippolytus detailed how and where the Gnostics – who believed

it was their secret knowledge, rather than God’s grace, that saved them – and

others got it all wrong.

Comprising ten volumes, historians consider his Book I as the most authoritative and important. Yet some – like Books II and II – appear lost forever while Books IV to X are now available but sans the author’s name though they were eventually attributed to Hippolytus. They were allegedly found in the monastery in Mount Athos in 1842.

Comprising ten volumes, historians consider his Book I as the most authoritative and important. Yet some – like Books II and II – appear lost forever while Books IV to X are now available but sans the author’s name though they were eventually attributed to Hippolytus. They were allegedly found in the monastery in Mount Athos in 1842.

Hippolytus’ authority against heresy was underscored by his

accusation of Pope Zephyrinus who proposed the idea of modalism in which the

names ‘Father’ and ‘Son’ are merely different names for the same entity. He was

also in conflict with Callixtus who became pope in 217AD against whom he

levelled the same accusation. This was after he became the head of a respected

seminary and a bishop in or around Rome.

Owing to what he considered was a heretic papal authority, Hippolytus

soon installed himself as an antipope – the first of its kind – which mean he

would act and function like a pope although without vested authority. Interestingly,

despite remaining in schism with every in Church authority up until 235AD and

well after Callixtus had died (in 222AD), Hippolytus was never accused as a

heretic.

Hippolytus of Rome fresco (Image source: Crossroads Initiative)

Other than his reputation of challenging heresies, Hippolytus

was a strong protagonist of the Logos doctrine championed by the most notable

of Greek apologists, Justin the Martyr (100-165AD) who made the distinction

between Logos (the ‘Word’) and the Father with his ‘Second Apology,’ which he

presented to the then-Emperor Marcus Aurelius four years before he was martyred.

As an ethical conservative, it’s no surprise that Hippolytus would be shocked

by Pope Callixtus I’s decision to absolve Christians who were guilty of grave

sins including adultery.

All of this would have been notable enough but Hippolytus made

his name in other aspects as well. Chief among them were his arguments against

the Church authority of which the prickliest was the outrageous claim that

popes are infallible when they speak ex

cathedra.

Ex cathedra basically means “from the seat of authority relating to pronouncements of the pope that are considered infallible.” In other words, what the pope says must be flawlessly true (never mind that only God is truth perfected) and therefore all Catholics must accept them as truth.

Ex cathedra basically means “from the seat of authority relating to pronouncements of the pope that are considered infallible.” In other words, what the pope says must be flawlessly true (never mind that only God is truth perfected) and therefore all Catholics must accept them as truth.

Polycarp of Smyrna (Image source: Catholic4Life)

Hippolytus’ position was certainly not that of the Church and

he had the strength of credentials to challenge it. After all, his lineage was

impressive and formidable, traceable to apostolic succession all the way to the

Apostle John, Jesus’ beloved disciple. He was a pupil of Irenaeus of Lyons (130-202AD)

who was a disciple of Polycarp of Smyrna (69-155AD). In fact, Polycarp himself

was said to have known John personally. All this is to say that Hippolytus’

authority as a bishop had no legitimate challenge whatsoever.

With his ‘On Christ and the Antichrist’ as well as ‘Commentary

on the Prophet Daniel,’ Hippolytus was also a widely-recognised authority in

Christian eschatology, offering valued interpretation on biblical prophecies.

With the latter work being the oldest found scriptural commentary, Hippolytus interpreted Daniel’s seventy-week prophecy as weeks of literal years. In chapters 2, 7 and 8, he offered his explanation of the prophet’s paralleling prophecies – in agreement with the other Early Fathers – that Daniel was alluding to the Babylonians, Medo-Persians, Greeks and the Romans.

With the latter work being the oldest found scriptural commentary, Hippolytus interpreted Daniel’s seventy-week prophecy as weeks of literal years. In chapters 2, 7 and 8, he offered his explanation of the prophet’s paralleling prophecies – in agreement with the other Early Fathers – that Daniel was alluding to the Babylonians, Medo-Persians, Greeks and the Romans.

Hippolytus’ take on the prophetic events and their

significance is also Christological. In his insight, he believed that Rome

would be divided into ten kingdoms after which, the antichrist would emerge who

would oppress the saints. This in turn will bring about Christ’s Second Coming

followed by the Rapture and then the annihilation of the antichrist. Judgement would

come next and then the burning of the wicked.

In his other book, ‘On Christ and the Antichrist,’ which he wrote amidst the Christian persecutions by Septimius Severus, he chose to differ from his mentor, Irenaeus, by focusing on what prophecy meant for the Church during his time.

In his other book, ‘On Christ and the Antichrist,’ which he wrote amidst the Christian persecutions by Septimius Severus, he chose to differ from his mentor, Irenaeus, by focusing on what prophecy meant for the Church during his time.

Hipppolytus of Rome (Crossroads Initiative)

Almost two hundred years after his death, the Roman Catholic Church

venerated him as a saint. Strangely, even the popes concurred. Considering that

he was the first to be an antipope, this was all quite astounding and hardly

believable. Yet that was the case.

One theory behind this change of heart was that Hippolytus had

made up with Pontian while both of them were in exile. Apparently once that

happened, his past outspokenness against the wrongdoings, cruelty and doctrinal

oversights among the bishops of Rome could be set aside. Amazingly, even the fact

that with the massive backing of the Roman population he went into opposition

against the bishopric was also forgiven.

But perhaps one sticky issue remained contentious –

Hippolytus’ authority on heresy and his insistence that some popes of his day

were heretics continued to be a thorn with the Church. In 1870 when the Vatican

Council decreed that popes were infallible, most of the scholars strongly

disagreed, displaying a common discord that was no doubt inspired by

Hippolytus.

Statue of Hippolytus (Image sources: Everett Ferguson Photo Collection and Trinities respectively)

In 1551, while excavating along the Tiburtine Road near where

an ancient church once was, workmen came across a marble statue bearing a

seated figure that looked like a bishop wearing a pallium (woollen vestment symbolising

full episcopal authority conferred by the pope).

On both sides of the seat were

carved the Paschal cycle, which displayed all the moveable feasts that occurred

ten weeks prior to and seven weeks after the Pascha (Easter). At the back of

the statue were titles of writings that were all attributed to Hippolytus.

It didn’t take long for Pope Pius IV to declare that the

figure was none of than that of Hippolytus.

Further

Reading Resources

1. Aland, Kurt (1970) Saints and Sinners – Men and Ideas in the

Early Church (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Saints-sinners-ideas-early-church/dp/B0006CPJSU

2.

Brent, Revd Allen (Jun 1995) Hippolytus

and the Roman Church in the Third Century: Communities in Tension Before the

Emergence of a Monarch-Bishop (Leiden: E.J. Brill, Vigiliae Christianae, Supplements (Book 31)).

Available at https://www.amazon.com/Hippolytus-Roman-Church-Third-Century/dp/9004102450

3. Calendarium Romanum in Libreria Editrice Vaticana (1969). Accessible online at https://archive.org/details/CalendariumRomanum1969

4.

Cerrato, J. A. (Oct 2002) Hippolytus Between East and West: The

Commentaries and the Provenance of the Corpus (Oxford Theological Monographs) (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

First Edition). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Hippolytus-between-East-West-Commentaries/dp/0199246963

5. Cross, F. L. and Livingstone,

E. A. (Jun 2005) The Oxford Dictionary of

the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, Third Revised

Edition). Available at https://www.amazon.co.uk/Oxford-Dictionary-Christian-Church/dp/0192802909

6.

Daley, Brian E. (Dec 2002) The Hope of the Early Church: A Handbook of

Patristic Eschatology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Hope-Early-Church-Patristic-Eschatology/dp/0801045975

7. Dunbar, David G. (Fall 1983) Hippolytus of Rome and the Eschatological

Exegesis of the Early Church in Westminster Theological Journal 45 (1983).

Pages 322-423 accessible online at http://www.galaxie.com/article/wtj45-2-04

(subscription required to read the whole article)

8.

Dunbar, David G. (Dec 1983) The Delay of the Parousia in Hippolytus

in Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 37 Nr. 4 (Leiden: Brill), p.313-327. Accessible

online at http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/157007283x00205

or https://www.jstor.org/stable/1583543?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

9. Durant, Will (Dec 1980) Caesar and Christ (The Story of Civilisation

III) (Simon & Schuster, 21st Printing Edition). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Caesar-Christ-Story-Civilization-III/dp/0671115006.

Also accessible online in PDF format at http://www.daniellazar.com/wp-content/uploads/Durant-Christ-and-Civ.pdf

10.Easton, Burton Scott (Sept 2014 [originally published 1934]) The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus Translated by Burton Scott Easton

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Apostolic-Tradition-Hippolytus-Burton-Easton/dp/1107429080

11. Froom, Le

Roy Edwin (1950) The Prophetic Faith of Our Fathers, Vol. 1

(Washington D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association). Accessible online

in PDF format at http://documents.adventistarchives.org/Books/PFOF1950-V01.pdf

12. Grant, Robert McQueen (1970) Augustus to Constantine: The Thrust of the

Christian Movement into the Roman World (New York, NY: Harper & Row,

First Edition). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Augustus-Constantine-thrust-Christian-movement/dp/B0006CAHNM

13. Hippolytus (author) and Behr,

John (editor) and Stewart-Sykes, Alistair (introduction and translator) (Sept

2015) On the Apostolic Tradition (Crestwood,

NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Popular Patristic Series). Available at https://www.bookdepository.com/On-the-Apostolic-Tradition-Alistair-Stewart-Sykes/9780881415209?redirected=true&utm_medium=Google&utm_campaign=Base4&utm_source=MY&utm_content=On-the-Apostolic-Tradition&selectCurrency=MYR&w=AFFZAU9SKJT5YRA80CPQAD31&pdg=kwd-311080623836:cmp-803526156:adg-43131497992:crv-196796817021:pid-9780881415209&gclid=CjwKCAjwzrrMBRByEiwArXcw22PHIiIogP9AzdgaPVV9p_LatNd1xxWnDX69f19PVNuyU1aEmtNWORoCEY8QAvD_BwE

14. Kirsch, Johann Peter (1910) St.

Hippolytus of Rome in The Catholic Encyclopaedia (New York, NY: Robert

Appleton Company). Retrieved August 9 2017 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07360c.htm

15. Lake, Kirsopp and Lawlor, Hugh

Jackson and Oulton, John Ernest Leonard (1926) Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea, The Ecclesiastical History with an

English Translation, Volume I (London: William Heinemann). Accessible

online at https://archive.org/details/ecclesiasticalhi01euseuoft

16. Mansfeld, Jaap (Mar 1992) Heresiography in Context: Hippolytus’

Elenchos as a Source for Greek Philosophy (Leiden, Brill Academic

Publishers, Philosophia Antiqua Book 56). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Heresiography-Context-Hippolytus-Philosophy-Philosophia/dp/9004096167

17.Pirlo, Ft. Paolo O. (1997) My First Book of Saints: Illustrated Lives

of Saints for Young Catholics (Paranaque City, Philippines: Sons of Holy

Mary Immaculate). Available at http://www.elib.gov.ph/details.php?uid=eb0623c07a36763cff096c3a38aeff8d&tab=2

18. Quasten, Johannes (Oct 1983

[originally published 1950]) Patrology

Vol. II – The Ante-Nicene Literature After Irenaeus (Allen, TX: Christian

Classics). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Patrology-Vol-Ante-Nicene-Literature-Irenaeus/dp/0870610856

19. Roberts, Revd. Alexander and Donaldson, Sir James and Coxe, Arthur

Cleveland, editors (May 2007 [originally published 1885]) The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325

Volume I – The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus (New York,

NY: Cosimo Classics). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Ante-Nicene-Fathers-Writings-D-Apostolic/dp/1602064695

20.Rostovtzeff, Michael Ivanovitch (1926) The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire (Oxford at the

Clarendon Press, First Edition). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Social-Economic-History-Roman-Empire/dp/B001QR0UMO

21. Saint Hippolytus of Rome in Encyclopædia Britannica

Online 2017. Retrieved August 7 2017 from Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Hippolytus-of-Rome

22. Wace, Henry (author) and Piercy, William C. (editor) (May 1994) A Dictionary of Christian Biography: And

Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D. With an Account of the

Principal Sects and Heresies (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers).

Available at https://www.amazon.com/Dictionary-Christian-Biography-Literature-D/dp/1565630572

23. Wordsworth, Christopher (1853) St. Hippolytus and the Church of Rome in the

Earlier Part of the Third Century from the Newly Discovered ‘Refutation of All

Heresies’ (London: Rivingtons). Available at http://www.worldcat.org/title/st-hippolytus-and-the-church-of-rome-in-the-earlier-part-of-the-third-century-from-the-newly-discovered-refutation-of-all-heresies/oclc/907380957?referer=di&ht=edition

Accessible online by University of California at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b246883;view=1up;seq=5

and also at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t8jd4sm1p;view=1up;seq=6.

Also available online by Harvard University at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044081740235;view=1up;seq=15

No comments:

Post a Comment