Scots React to Laud's Interference

Khen Lim

Image source: regenerationandrepentance.wordpress.com

After James I brought the world its most cherished Bible, his

son Charles I did all he could to become England’s first and only monarch to be

beheaded and before that, he tried hard to strongarm the Churches of England

and Scotland to kneel to him and to do that, he fatally appointed a tyrannical monster

to the chair of Archbishop of Canterbury.

In contrast to how the previous rule had a listening ear, Laud

was dead to the Puritans. In fact his evidently heavy persecuting hand not only

landed Puritans like Alexander Leighton, William Prynne, John Bastwick and Henry

Burton in gaol but they were also badly tortured and mutilated along the way. In

many cases, their ears were cropped and faces branded. Puritans like them only wanted

to expunge all erroneous or superstitious Catholic elements from the Church of

England but for that, they ran headlong into Charles and then Laud. Their

revolt against the king was exclusively about preserving their Puritan faith

for which they suffered tremendously.

Despite Cranmer’s popular Book of Common Prayer book first

introduced in 1548 during Edward VI’s reign (Charles’ god-granduncle), Laud

believed his new version was better than his revered – and martyred –

predecessor’s. He sought to use it to compel everyone to its former practice

and power. He was so determined to make people bow at the Name of Christ and

compel them to adhere to his newly-introduced services that it all turned

horribly pear-shaped instead.

Throughout England and Scotland, the people were outraged and

mortified that they could not have their services untouched. Some of the

congregations were so furious and upset that wisely, their bishops retained

their old formats. In Edinburgh, Scotland, the situation was especially

pronounced at the St Giles’ Cathedral where Charles had his Scottish coronation

service in accordance to Anglican rites hardly four years ago. There, the church

leaders decided that on this day in 1637, they would unwaveringly inaugurate Laud’s

revised – but reviled – Anglican Book of Common Prayer. In the land of

Presbyterianism, this book of canons was a serious threat to its intended

demise and it came the way of a royal edict through to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Image source: from-bedroom-to-study.blogspot.com

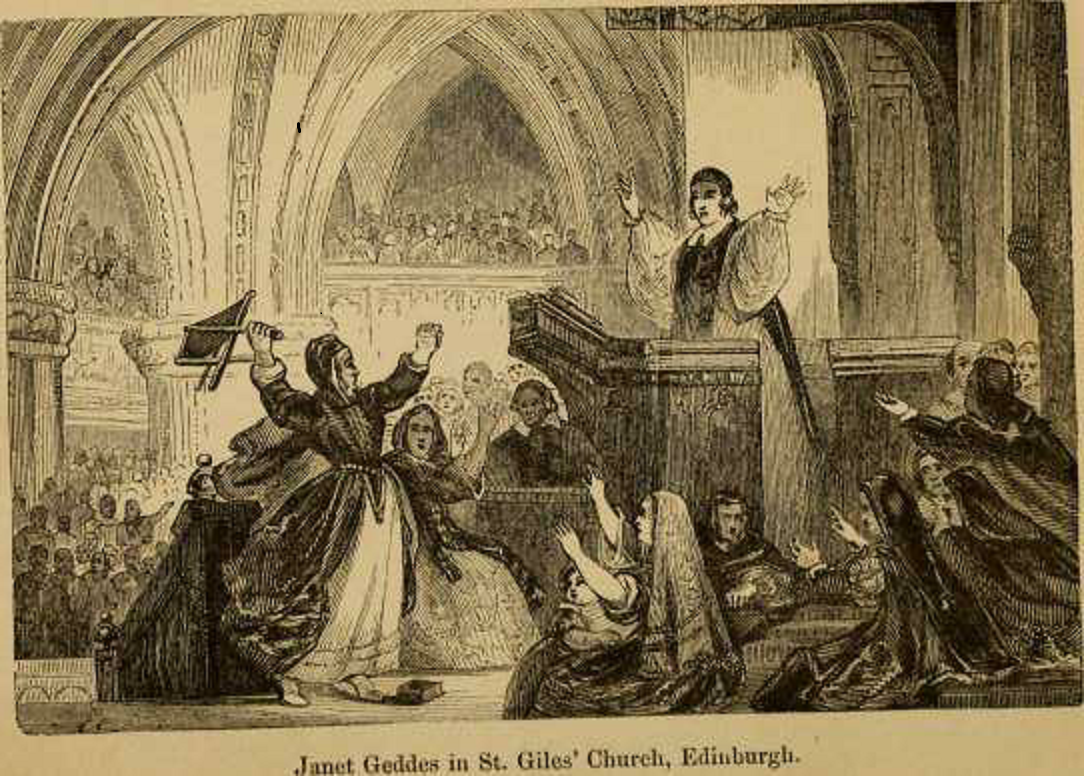

To their dismay, as James Hannay, Dean of Edinburgh carried

out the new rituals, the congregation turned uproarious, branding him a ‘devil

spawn.’ Right at that very instant, a market-woman in her late thirties by the

name of Jenny Geddes was so incensed that she hurled her stool directly at him,

shouting, “Devil cause you colic in your stomach, false thief: dare you say the

Mass in my ear?”

By then, everyone else in the congregation was either screaming

abuse or throwing Bibles, sticks, stones or stools. Inevitably, officers

summoned by the Provost threw out the rioters but it was too late. Laud’s

insensitivity by now had effervesced into something far larger and less

controllable as serious riots now flowed on to the streets and erupted in other

cities as well. The Provost and magistrates found themselves under siege in the

City of Chambers and quelling could only come once negotiation began with the

rioters themselves.

But these negotiations went nowhere. In his now-infamous

pigheadedness, Charles threw the Scottish petitions out of the window and so

none of their demands were met, ensuring another round of riots but this time,

leading to talk of civil war, until the National Covenant was signed the

following year in 1638 in which there was to be an unconditional revocation of

so-called innovations like the Prayer Book until or unless it has been

scrutinised by the Scottish Parliament and the General Assembly of the Church.

But when the bishops and archbishops were expelled from the Church of Scotland

later in the same year, Charles launched the Bishops’ Wars that spiralled out

of control to eventually become the Wars of Three Kingdoms.

Nobody really could tell how the details all piece together in

trying to link the riots to the eventual civil wars. In fact some even cast

doubts as to whether Jenny Geddes did exist and was the catalyst behind the

civil war or not or if it was possibly an imagined icon of Scottish

pugnaciousness in the face of English interference. If it were, it was hard to

tell since there is a memorial in her name at St Giles’ today with a sculptured

three-legged cuttie-stool.

The beheading of William Laud in 1645 (Image source: executedtoday.com)

As for William Laud, 1640 was not a good year. He was arrested

for treason and thrown into gaol at the Tower of London amidst the English

Civil War between Charles’ Royalists and Cromwell’s Roundheads. In the spring

of 1644, his trial produced no verdict but when Parliament took up the issue,

an attainder was passed, resulting, in the following year, in his beheading on

Tower Hill just as Anne Boleyn did a little more than a century earlier.

His autocratic, insensitive and ill-advised intrusion into

Scottish church polity and tradition via what he believed were high church

services proved costly to his life. Perhaps the cruellest irony for Laud was

that the judge who presided over his trial was none other than William Prynne sans

ears and featuring cheeks branded with the letters ‘S.L.’ to originally mean ‘Seditious

Libeller’ but which he turned it around to become ‘Stigmata Laudis,’ meaning ‘Sign

of Laud.’

Imagine that.

No comments:

Post a Comment