God Raises Kanzo Uchimura

On the Day February 13 1861

Khen Lim

Kanzo Uchimura (Image source: Geneugen van Nederland)

One-hundred and fifty-six years ago to this day, children were

born everywhere just like they would on any other day. In Japan, it was,

understandably, the same. What could ever be different, right?

It seemed God

took a different view and eight years after Commodore Perry anchored in the Bay

of Yedo (Tokyo Bay), in the midst of Edo (today’s Tokyo) in the compound of the

daimyo (feudal lord) was born a little boy who would emerge from the elite

Samurai class to spiritually impact his nation as well as the world. His name

was Kanzo Uchimura.

From young, Uchimura displayed great talent for languages.

Although in his modest, he felt his English wasn’t good enough, the reality was

that he began learning the language at the age of 11 when he returned to Tokyo

after five years of tutelage at the capital of his own Takasaki clan.

By the

time he was 13 years of age, his parents enlisted him at the Gaikoku Gogaku

(tr. foreign language school) with the hope that he could successfully prepare

for the Kaiseigakko (now Tokyo Imperial University) from which he could then

embark on a career within the government.

Three years later, at 16 years old, Uchimura was offered a

place to study at the newly-opened Imperial College of Agriculture in Sapporo (today’s

Hokkaido University) where the medium of instruction was exclusively English.

There, he was to encounter the influence of two Americans, William S. Clark and

Merriman C. Harris, the latter of whom somehow managed miraculously to have a

whole class of freshmen baptised on the night before Uchimura arrived.

William S Clark (Image source: Wikipedia)

Clark, a graduate of Massachusetts-based Amherst College who was

also the College President had been aiding the Japanese government for a year

to set up the college, was employed to teach agricultural technology but more

importantly, he was a devoted lay missionary who shared the Gospel very

successfully through Bible classes. Like Harris, Clark had all his students

converted and all signed the ‘Covenant of Believers in Jesus’ in which everyone

bore the commitment to continue studying the Bible and do all they could to

live morally upright lives in glory to God.

Given the remarkable circumstances, even Clark’s return to the

United States a year later did nothing to prevent Uchimura from being swept off

his feet. The influence of the small Covenant group he left behind was all but

complete and following pressure from his persuasive seniors, the 16-year-old

ultimately committed to the Covenant himself in his freshman year but it was

only in June 1878 that he was finally baptised by a Methodist missionary. Of

course, it helped that he mastered the English language enough to read

proficiently and follow Christian manuscript from which he was converted and

later, baptised.

From the point onwards, Uchimura decided to focus intently on

his profession of faith and so on Graduation Day in 1881, he pledged to

collaborate with two other fellow converts to centre their efforts on two ‘J’

priorities – Jesus and Japan. While Clark was an inspiration to him, his

relationship with Harris was not without its notable differences particularly

when the latter was serving as the leader of the church that was established by

the new students and a few adults.

These altercations eventually gave rise to Uchimura working

with seven other brothers in Christ to found an independent church, free of

denominational complications. It was this formation that invariably served as

the blueprint for his later Non-Church assemblies, the first of which was in

Sapporo, Japan. It was inevitably Clark whose teaching and exemplary spiritual

values that convinced Uchimura and his friends that they too could practise the

conduct of authentically living by faith free of any reliance on a religious

body or a professional clergy.

After that, he went into service for his country. By 1884,

however, his first marriage, brief as it was, came to an unhappy end but it

probably also gave him even more impetus to further his studies in which he was

intent on learning about ‘practical philanthropy.’

Wistar Morris (Image source: Overbrook Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, Penn.)

To that end, he once again left

for America where he met up with a Quaker couple, Wistar Morris and his wife, who

then arranged for him to serve under Isaac N Kerlin, the superintendent of the

Pennsylvania Institute for Feeble-Minded Children in Elywn, Delaware. From

Morris, Uchimura was greatly influenced by the Quaker faith and pacifism that

it left a lasting impression on him.

Uchimura was at the Pennsylvania Institute for eight stressful

months. Finally he resigned and then resorted to travel through the New England

seaboard where he enlisted himself at the Amherst College in September 1885,

likely inspired by Clark, his earlier mentor during his more youthful days in

Japan.

Prof Julius H Seelye, professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy, Amherst College (Image source: Amherst College)

There, he met Julius Hawley Seelye, the college president. It was

he who Uchimura said had revealed before him, the “evangelical truth in

Christianity.” In fact when Uchimura was struggling with his concern for

personal spiritual growth, it was Seelye who set him straight.

The college president said to him, “Uchimura, it is not enough

just to look within yourself. Look beyond yourself, outside of yourself. Why

don’t you look to Jesus, who redeemed your sins on the Cross and stop being so

concerned about yourself? What you do is like a child who plants a pot plant,

then pulls up the plant to look at the roots to see if the plant is growing

satisfactorily. Why don’t you entrust everything to God and sunlight and accept

your growth as it occurs?”

To Uchimura, Seelye was larger than life. Not only did he

accept his advice but it was on this acceptance that he finally began to

actually experience the deepening of his own faith and the real awakening of

his spiritual self.

Here was a man who took over where Clark left years ago,

becoming his enduring spiritual mentor. “He is my father in faith. For forty

years, since then, I preached the faith taught me by that venerable teacher,”

Uchimura wrote.

Hartford Seminary today, photo taken 2009 (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

It was Seelye who then encouraged him to attend the Hartford

Theological Seminary, that was, after he had completed his second Bachelor of

Science degree program in General Science first. However, his time at the

Seminary was short-lived – Uchimura quit after merely one semester and returned

home in 1888. His theology studies had left him disappointed and there could

possibly be two reasons behind this.

To begin with, the significant cultural differences between

what he’d come to learn in America and what might or might not be applicable to

Japan could have raised questions as to relevance but more significantly, it

was the petty bickering he observed among the various denominations that not

only turned him off but probably settled for him, the idea of a church that was

independent of such issues.

Following his graduation, Uchimura returned home in 1888 where

he then began his vocation as a teacher posted in a number of schools. However,

one school after another, he inevitably tendered his resignation over conflict

of principles. It was his uncompromising attitude that resulted in him losing

his job time and again. He could not accept how authorities and/or foreign

missions controlling the schools that he taught at.

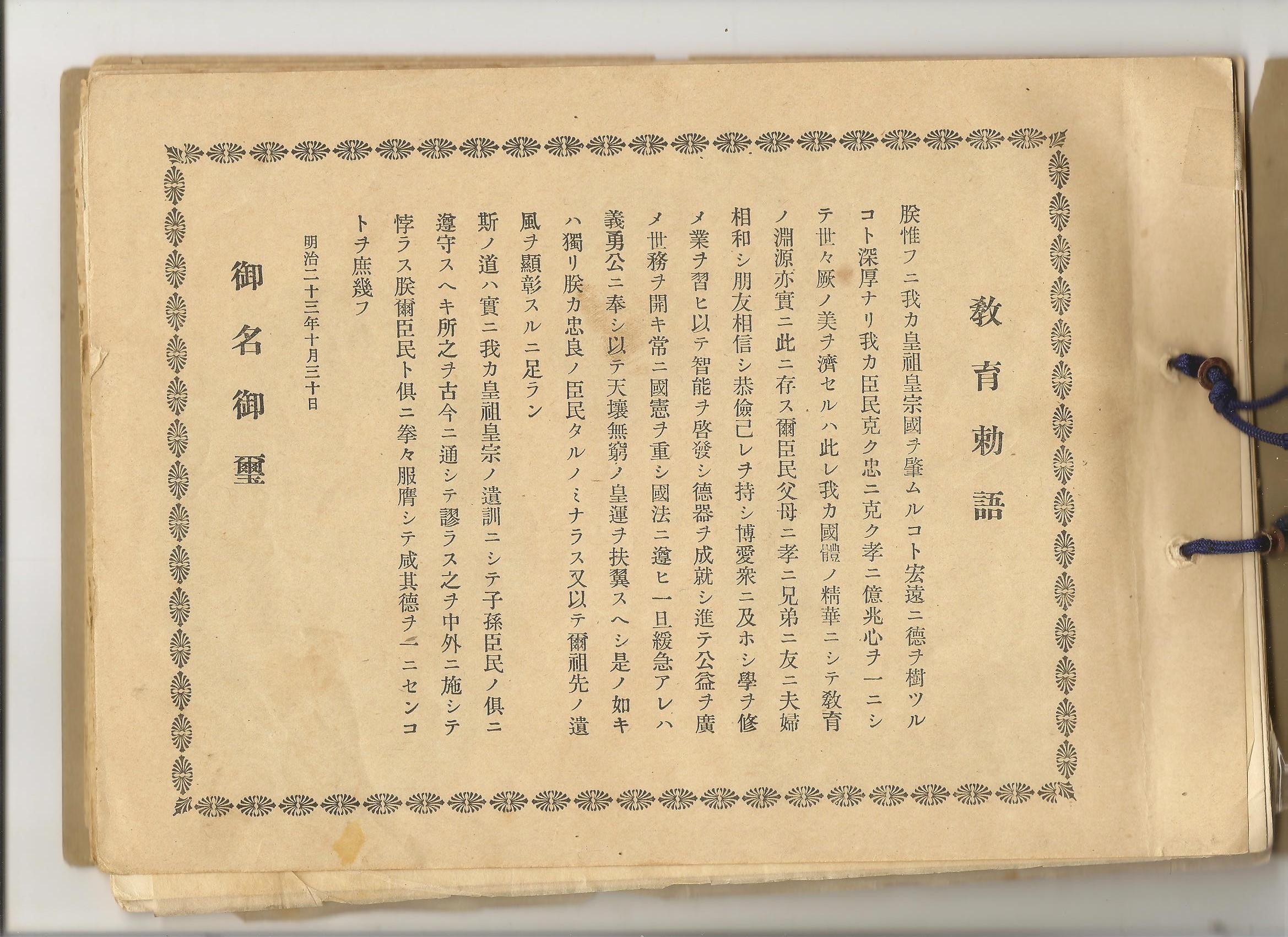

An example of an Imperial Rescript on Education (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

In one incident in 1891 where he was a teacher at the First

Higher School in Tokyo (at that time, a preparatory division for the Tokyo

Imperial University), he refused to comply with the order to bow before the

portrait of Emperor Meiji and his signature featured on a copy of the new

Imperial Rescript on Education at a formal ceremony. He later had a change of

heart and from his sickbed, he assigned a colleague to go bow on his behalf but

by then, his career in education was already shot to pieces.

Uchimura had this to say:

“On my return to Japan in 1888, I made several attempts to put

my educational ideas to practice but always failed. Missionaries nicknamed me a

‘school-breaker’ because wherever I taught, troubles arose and schools were put

in jeopardy. My fortunes in Government schools were worse. My refusal to bow to

the Imperial Rescript on Education, not only deprived me of my situation in the

Dai Ichi Kotogakko but sent me out into Japanese society as a vagabond wherein

for some twenty years, I had not a place where to lay my head on.”

By now, Uchimura realised that his spiritual beliefs had

gotten in the way of his teaching career. This incompatibility defined the

reason why he stood up for the principles of his faith. He simply felt that

with his teaching career, he could not dilute his spiritual integrity in his

devotion to Christ but instead he found a far better outlet in being able to

write.

It was in 1895 that Uchimura became a senior columnist for the

popular local newspaper, the Yorozu Chōhō

(tr. Myriad Reports) and there, he achieved stunning success. Once he had

established his fame and popularity as a renowned writer, he launched some

salvos at industrialist Ichibei Furukawa, owner of the Ashio Copper Mine, for

his notoriety in modern Japan’s earliest-known industrial pollution scandal.

Three years later, in 1898, Uchimura began his own magazine beginning

with Tokyo Zasshi (tr. Tokyo Journal

or Tokyo Independent) before he turned it, in 1900, into another one called Seisho no Kenkyu (tr. Bible Study),

which went for 357 issues until his death thirty years later. With persuasion

from his long-time friend from Sapporo, Nitobe Inazō, who also helped him in

the formation of the Friends School in Tokyo, he commenced teaching Bible

Studies every Sunday as well.

Nitobe Inazo, Japanese Ethical professor, friend of Uchimura (Image source: year40philosophy.wordpress.com)

Interestingly, Inazō was then the president of the First

Higher School in which Uchimura had refused to bow before the portrait of the

emperor. It was from all of these activities that Uchimura’s vision of the

Non-Church Movement began to crystallise. It was also from them that he became

the most compelling voice of Japanese Christianity of that time.

Still Uchimura was not without his burdens. His endearing

concerns for the poor and the handicapped would become something he’d

shouldered for the rest of his life but at the same time, it was this, among

others, that moulded him to be the person he eventually became.

As he stayed

away from the formalised church settings he had come to know during his studies

in America, he slowly gravitated towards what he preferred to call it, a

‘non-church’ approach. His understanding was that while believers need one

another – as in fellowship – that did not necessarily be defined rigidly as a

bricked or wooden sanctuary. In other words, fellowship did not hinge on an

actual physical church contextually bound by a regulated setting.

Furthermore, Uchimura’s faith in Christ proved costly in Japan

where Christianity remained unpopular. For him, finding jobs was difficult. As

he discovered, whatever job he came across and accepted, he would soon lose it

because he refused to allow his faith to be compromised. Yet he knew he needed

employment to stay financially afloat but again, he steadfastly rejected all

offers of mission funds.

At the same time, the pacifism that the Quaker family had

inspired in him brought him greater troubles as he sought to use his newspaper

columns to rail against Japan’s war against Russia. Needless to say, his views

did not dovetail with the more hawkish editorial opinion.

None of this worked well with his career as a journalist and

soon, even this came to an end. Still he relentlessly grounded on through

preaching where, in 1918, he began to command audiences of 500 to 1,000 in

rented halls in downtown Tokyo. One of these was the Hygienic Hall, located at

the front of the Home Department, near the Imperial Castle. These classes

lasted till 1923 when it was abruptly interrupted by the 7.9 Richter

Tokyo-Yokohama Earthquake of 1923, also called the Great Kanto Earthquake where

over 140,000 died as a result.

Uchimura in a Bible class, 1924 (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

After that, Uchimura resumed the classes but on a smaller

scale. Still, he considered himself fiercely independent and a freelancer of

his own religious standing. He had no church to belong to and neither was he

‘licensed’ by an ecclesiastical body to preach. In a church sense, he was a ‘persona non grata.’

It was through these exposures that his concerns for the poor

and the suffering had earned him not just local admiration but worldwide

recognition at the same time. Needless to say, by way of his preaching, his

teaching skills came in very handily.

At the same time, he used his writing skills to publish books

with resounding impact such as Nihon oyobi Nihonjin (tr. ‘Japan

and the Japanese’ but later became known as Daihyoteki

Nihonjin or ‘Representative Men of Japan’) in 1894 and then Yo wa Ikanishite Kirisuto

Shinto to Narishika (tr. ‘How I

Became a Christian’) the following year, that influenced a whole

emerging generation of Japanese intellectuals to the extent that some had

become Bible readers, though not Christians. In fact his books became very

well-known and were translated into different languages for a wider readership way

beyond Japan and the usual English-speaking countries.

“My two books, which I wrote in English were translated into

several European languages, enabling me to find many friends in the continental

Europe. The books failed in America; Englishmen never liked them. I pass for a

rabid ‘yaso’ (follower of Jesus) among my countrymen and a heretic and

dangerous man among missionaries and their converts in this country. Still I

seem to have not a few friends in this wide world; for my magazine – the

Bible-magazine written in my own language – has quite a large circulation and

my books translated into German are still being read in Europe,” Uchimura

wrote.

Uchimura resting at the foot of Mount Nasu, Tochigi Prefecture, Japan (Image source: Pinterest)

Through his preaching, he began to have his own followers who

adhered to his idea that an organised church might not necessarily be very

productive. Uchimura’s attitude, for better or for worse, was such that even

Christian sacraments like baptisms and communion were unnecessary for salvation

under Christ.

To all of this radicalism, he called it ‘Mukyōkai,’ which means

the Non-Church Movement. The movement proved powerful and widespread as it

attracted many students in Tokyo who would go on later in life to become the

crux of the nation’s influential academia, industry and literati. Through this

following, Uchimura’s views on religion, politics, science and socioeconomics

found a willing channel for change in society.

Uchimura's grave with the inscription, 'I for Japan. Japan for the World. The World for Christ. And All for God' (Image source: findagrave.com)

Kanzo Uchimura, the irrepressible thinker and practitioner of

Christ, and the son of a Takasaki Clan samurai died in 1930. By then, his

reputation had grown beyond his dreams while the followers of his Non-Church

movement carried on his legacy and produced a prodigious amount of literature.

On his tomb, his followers added an expression that he himself penned in his

favourite Bible – “I for Japan. Japan for the World. The World for Christ. And

All for God.”

Uchimura (seated left) with his second wife (standing left) whom he apparently married in 1893 (Image source: Wikimedia)

Uchimura wrote in March 1926, saying, “I am a Japanese by

birth and a Christian in faith and my Christianity made me a ‘Bürger der Welt,’

a world citizen, a brother to humanity. With the managing editor, I am an

advocate of peace. Both of us are haters of war. We take comparatively little

interest in politics. But we love God, the world, the soul.”

The Uchimura Kanzo Memorial Stone Church built in 1988 by American architect Kendrick Kellog in Kitasaku-gun, Nagano, Japan (Image source: Ikedane Nippon). For more information about the church, go here.

“I love two J’s and no third; one is Jesus and the other is

Japan. I do not know which I love more, Jesus or Japan. I am hated by my

countrymen for Jesus’ sake as foreign belief and I am disliked by foreign

missionaries for Japan’s sake as national and narrow. Even if I lose all my

friends, I cannot lose Jesus and Japan… Jesus and Japan; my faith is not a

circle with one centre; it is an ellipse with two centres.

“My heart and mind

revolve around the two dear names. And I know that one strengthens the other;

Jesus strengthens and purifies my love for Japan and Japan clarifies and

objectives [sic] my love for Jesus. Were it not for the two, I would become a

mere dreamer, a fanatic, an amorphous universal man.”

Uchimura’s Literary Contributions

- Uchimura Kanzo with notes

and comments by Taijiro Yamamoto and Yoichi Muto (1971) The Complete Works of Kanzo Uchimura (Tokyo, Japan: Kyobunkwan).

Available at https://www.amazon.com/Complete-Works-Kanzo-Uchimura/dp/B001P4PDBQ

- Uchimura, Kanzo (1894) Japan and the Japanese: Essays (Republished

by British Library, Historical Print Editions in March 2011). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Japan-Japanese-Essays-Kanzo-Uchimura/dp/124118626X

- Uchimura, Kanzo (1895) How I Became A Christian: Out of My Diary (originally

published by Keiseisha, Tokyo but republished by Cornell University Library in

May 2009). Available at https://www.amazon.com/How-became-Christian-out-diary/dp/1429778814

- Uchimura, Kanzo (1895) The Diary of a Japanese Convert (New

York: Fleming H. Revell Company). Available at https://archive.org/details/diaryofjapanesec00uchirich

- Uchimura, Kanzo (1908) Representative Men of Japan (Tokyo,

Japan: The Keiseisha). Available at https://archive.org/details/representativeme00uchirich

Reading Sources

- Atsuhiro, Asano (Jan 2011)

Uchimura and the Bible in Japan in

Lieb, Michael and Mason, Emma and Roberts, Jonathan et al (2011) The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History

of the Bible (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press). Available at https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/reader/0199204543/ref=sib_dp_ptu/254-4158393-2489602#reader-link

and also http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199204540.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199204540-e-23

- Caldarola, Carlo (Aug

1997) Christianity the Japanese Way (Monographs

and Theoretical Studies in Sociology and Anthropology in Honour of Nels

Anderson) (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Christianity-Monographs-Theoretical-Sociology-Anthropology/dp/9004058427/ref=la_B001JXNXOW_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1486707459&sr=1-1

- Cohen, Doron B. (1992) Uchimura Kanzō on Jews and Zionism in

Japan Christian Review 58, p118. Available at https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/4136

- Cortright, David (June

2008) Peace: A History of Movements and

Ideas (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Peace-History-Movements-David-Cortright/dp/0521670004

- Drummond, Richard H.

(1999) Uchimura, Kanzo in Anderson,

Gerald H., editor (Aug 1999) Biographical

Dictionary of Christian Missions (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans

Publishing), p137. Available at https://www.amazon.com/Biographical-Dictionary-Christian-Missions-Anderson/dp/0802846807

- Hiroshi, Shibuya and Shin,

Chiba, editors (Nov 2013) Living for

Jesus and Japan: The Social and Theological Thought of Uchimura Kanzō

(Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Living-Jesus-Japan-Theological-Uchimura/dp/0802869572

- Howes, John F. (Jan 2006) Japan’s Modern Prophet: Uchimura Kanzo,

1861-1930 (Asian Religions and Society) (Vancouver, British Columbia:

University of British Columbia Press). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Japans-Modern-Prophet-1861-1930-Religions/dp/0774811463

- Jennings, Raymond P.

(1958) Jesus, Japan and Kanzo Uchimura: A

Study of the View of the Church of Kanzo Uchimura and Its Significance for

Japanese Christianity (Tokyo, Japan: Kyobunkwan, Christian Literature

Society). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Jesus-Japan-Kanzo%C3%8C%C2%84-Uchimura-significance/dp/B0007J93ZC

- Miura, Hiroshi (Feb 1997) The Life and Thought of Kanzo Uchimura,

1861-1930 (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Life-Thought-Kanzo-Uchimura-1861-1930/dp/0802842054

- Moore, Ray, editor (Feb

1982) Culture and Religion in

Japanese-American Relations: Essays on Uchimura Kanzō, 1861-1930, Michigan

Papers in Japanese Studies Book 5 (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Centre

for Japanese Studies). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Culture-Religion-Japanese-American-Relations-Uchimura/dp/0939512106

- Neill, Stephen (Jan 1964) A History of Christian Missions (Pelican

History of the Church, Vol. 6) (London, U.K.: Penguin). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Christian-missions-Pelican-history-Church/dp/B0000CM1FY

- Rustow, Dankwart A.,

editor (1970) Philosophers and Kings;

Studies in Leadership (New York: George Braziller, Inc.). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Philosophers-Studies-Leadership-Dankwart-Rustow/dp/0807605395

- Uchimura, Kanzo (1861-1930)

in Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures (Tokyo, Japan: National Diet

Library). Available at http://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/datas/240.html

- Willcock, Hiroko (Aug

2008) The Japanese Political Thought of

Uchimura Kanzo (1861-1930): Synthesising Bushido, Christianity, Nationalism and

Liberalism (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press). Available at https://www.amazon.com/Japanese-Political-Thought-Uchimura-1861-1930/dp/077345151X

No comments:

Post a Comment